We were fortunate to be joined on one of our MuchLoved Modules by grief expert, John Wilson. Here we explore six myths of coping with loss that John sets out to dispel and look at how people experience grief differently.

We often hear about the five stages of grief as identified by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross: Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression and Acceptance. What may be news to many is that this framework was not original but based on earlier work by John Bowlby and Colin Murray Parkes, whose stages are: Shock-Numbness, Yearning-Searching, Disorganisation-Despair, and Reorganisation.

The Kübler-Ross stages were devised to help people come to terms with a terminal diagnosis, not a bereavement. Furthermore, they were meant only as a loose framework. According to John Wilson, the model is not helpful for people experiencing grief. Read an article on this topic.

A popular myth is that bereaved people need to ‘let it out’ or discharge their emotions in some way to come to terms with their loss, but this idea has been thoroughly disproven. Many people are naturally resilient and able to cope without experiencing intense grief and distress.

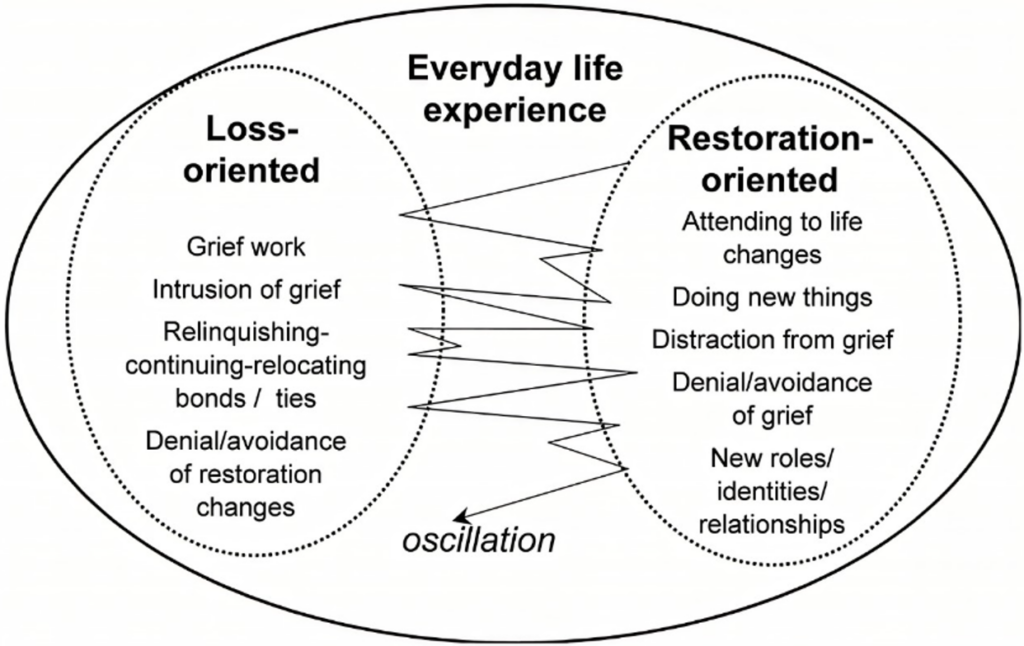

The Dual Process Model, by Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut, is a useful tool and shows that people can move between periods of grief whilst carrying on with their life.

Those who do not feel an intense sense of loss sometimes think there is something wrong with them, but there is no right or wrong way to grieve, and we all experience it in different ways. Family, friends, work and hobbies can provide a welcome source of comfort and distraction from grief.

Over time, most of us will adapt and learn to live with our grief. Grief counsellors observe that maintaining continuing bonds with a loved one is incredibly important. These bonds are unique and personal, but could include:

You do not need to let go of your loved one to move on. Instead, these continuing bonds can help you to move forward, whilst maintaining an enduring connection, taking your loved one with you into the future.

It is important to think about what to say and do when relating to newly bereaved people. They can feel hurt or angry at the reaction that others have to their grief, and we should not underestimate the harm done by avoiding talking to them.

Bereaved people should not have to worry about managing their own grief so that others don’t feel uncomfortable.

If a friend or family member has lost someone, don’t try to cheer them up or change the subject. It’s ok if you don’t know what to say. Tell them that you don’t know what to say and just be there for them. Simply be with them in their grief.

This is a particularly difficult area according to John Wilson. He believes there is such a thing as grief disorder, whereby people experience prolonged or chronic grief, but this is rare. The word disorder matters in countries where a diagnosis is required to access counselling (e.g. the US).

People who experience severe, complex grief disorder can get through it with the help of a skilled grief counsellor. For others, the experience is less intense and they will recover gradually, with time and support. Around half of people will grieve healthily and do not need the help of counsellor. Whether or not to seek counselling is a personal choice for each bereaved person, whatever the nature of their grief.

Typically, bereaved people will go on grieving but will reconcile and adapt, learning to live with their grief. John Wilson has spent many years researching what people do that eventually makes life easier:

If you would like to watch John Wilson’s presentation, a recording of the MuchLoved webinar is available here.